Simon Garfield’s On the Map is the third book of its kind that I’ve encountered, akin to Mike Parker’s Map Addict (review) or Ken Jennings’s Maphead (review): Maps 101—an introductory book for people who are interested in maps but don’t necessarily know a lot about them, written by an enthusiastic generalist. But Garfield’s book is more peripatetic and less focused than the others.

Simon Garfield’s On the Map is the third book of its kind that I’ve encountered, akin to Mike Parker’s Map Addict (review) or Ken Jennings’s Maphead (review): Maps 101—an introductory book for people who are interested in maps but don’t necessarily know a lot about them, written by an enthusiastic generalist. But Garfield’s book is more peripatetic and less focused than the others.

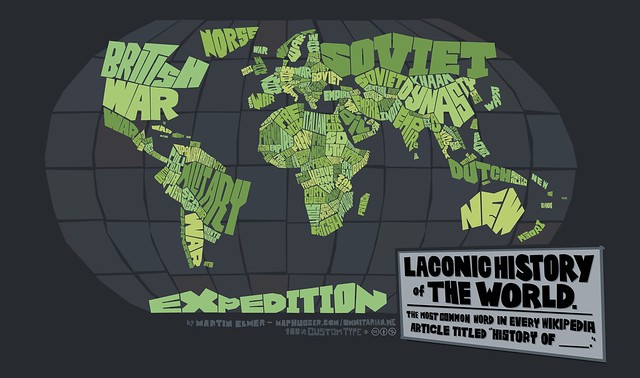

On the Map covers a huge amount of ground in its 400-plus pages, from the Library of Alexandria to Apple Maps (but only the announcement; the subsequent fracas came too late). There is no narrative thread tying the chapters together, and some chapters, arranged by theme, span centuries; they’re interspersed with sidebars called “pocket maps” that deal with a smaller subject in a bit more depth. It’s an excellent survey of what’s been happening with maps over the past decade; you’d be better served by reading this book than by plowing through eight years and 4,055 posts of my former map blog, though you’d arrive at the same point in the end.

Because of that blog, I am the worst audience for this book: nothing really surprised me. Those who have been paying close attention to this subject will not find much new material: this is a survey. In fact, there were several instances where I knew that Garfield was telling the story too briefly, and leaving stuff out. In his rush to cover everything, he glosses over a lot of detail. Prodigious in scope but limited in depth, this book is a view from a height. There are chapters, even paragraphs, whose topics have been addressed with entire books. On the Map is only the start of your trip into maps; it will only whet your appetite for more.

Previously: On the Map: A New Book from Simon Garfield.

Amazon | iBooks | author’s page | publisher: UK, USA