Chet Van Duzer’s presentation about the lack of empty spaces on old maps—horror vacui—at the November 2017 meeting of the New York Map Society has now been uploaded to YouTube.

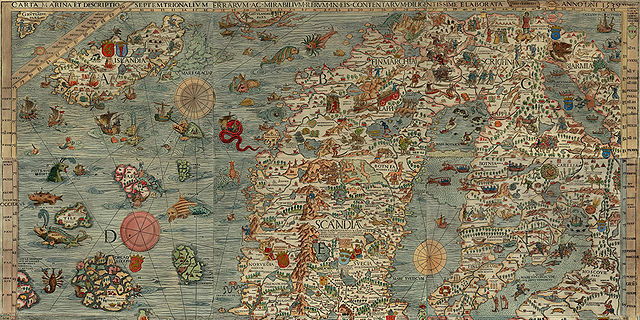

As I’ve said before, the subject of empty spaces on maps is of considerable interest to my own research on fantasy maps: fantasy maps tend to be full of empty spaces not germane to the story, whereas real-world maps were covered in cartouches, sea monsters, and ribbons of text. As a result I’m very interested in what Van Duzer has to say about the subject, and have been looking for something exactly like this recorded talk for some time.

I wasn’t disappointed. Van Duzer lays out, with some particularly over the top examples, how empty spaces on maps were consumed (his term) by text, ships, sea monsters and other embellishments that were designed for that very purpose. Some of those embellishments were absolutely enormous, others curiously redundant: a single map does not need four identical scales or a dozen or more compass roses, for example. “Everything we’re seeing here was a choice on the part of the cartographer,” he says at one point; “all this information could be disposed differently.”

Previously: Horror Vacui: The Fear of Blank Spaces.