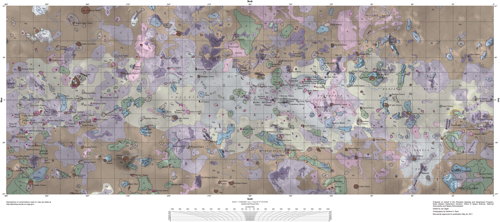

In my review of Paul Schenk’s Atlas of the Galilean Satellites I noted that the maps of Jupiter’s four largest moons were actually spacecraft imagery placed on a map projection; there were no non-photographic maps. In that context, the geologic map of Io, just out from the U.S. Geological Survey, is both novel and pertinent. The maps are based on Voyager– and Galileo-derived photomosaics of Io’s surface released in 2006, but they’re maps. ASU news release, Universe Today.

Month: March 2012

Old Maps Online

Ars Technica calls Old Maps Online “the world’s single largest online collection of historical maps” but that’s not strictly the case. When I first read that I thought: what, bigger than Rumsey? Rumsey has 30,000 maps; Old Maps Online has 60,000. But Old Maps Online is a portal, not a collection: it has a damn slick timeline-and-map interface that brings up maps from the online collections of five institutions (so far), including the British Library, the National Library of Scotland, and yes, the David Rumsey Map Collection. At first glance it seems like a good place to start if you’re looking for a map of a specific time and place (as I have done on many occasions), and if they add more institutions to their database it will be even more useful.

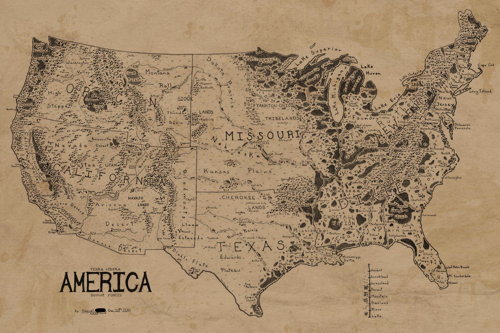

A Fantasy Map of the U.S.

Fantasy maps have a very specific style that is actually quite limiting. For an example of what would happen if all maps were subject to the same limitations as fantasy maps, have a look at what is described “a map of the United States à la Lord of the Rings”; it was posted to Reddit and edited there by divers hands. The version above had the gridlines removed and made more “antique.” It does look like the early Middle-earth maps done by Pauline Baynes and Christopher Tolkien. To match the movie maps, you’d have to replace all the text with overdone uncial calligraphy and Tengwar vowel marks, whereas maps in modern fantasy novels would lose the shading on the mountains and have all the text done in Lucida Calligraphy. Via io9.

Atlas of the Galilean Satellites

Paul Schenk’s Atlas of the Galilean Satellites (Cambridge University Press, 2010) collects all the imagery gathered by the Voyager and Galileo missions of the four major moons of Jupiter (Callisto, Ganymede, Europa and Io, all discovered by Galileo in 1610) and assembles them into global, quadrangle and area maps. But this heavy, 400-page tome begins with a confession. “This Atlas is not what it should be.” The failure of the high-gain antenna on the Galileo spacecraft meant that far less data could be transmitted back to Earth during its nearly eight-year mission than had been planned. Large tracts of the moons are mapped in low resolution; the fuzzy images yield little detail. But until another mission is sent—the Juno probe now en route to Jupiter will not be studying the moons—this is all there will be for the foreseeable future. For decades, in fact.

Paul Schenk’s Atlas of the Galilean Satellites (Cambridge University Press, 2010) collects all the imagery gathered by the Voyager and Galileo missions of the four major moons of Jupiter (Callisto, Ganymede, Europa and Io, all discovered by Galileo in 1610) and assembles them into global, quadrangle and area maps. But this heavy, 400-page tome begins with a confession. “This Atlas is not what it should be.” The failure of the high-gain antenna on the Galileo spacecraft meant that far less data could be transmitted back to Earth during its nearly eight-year mission than had been planned. Large tracts of the moons are mapped in low resolution; the fuzzy images yield little detail. But until another mission is sent—the Juno probe now en route to Jupiter will not be studying the moons—this is all there will be for the foreseeable future. For decades, in fact.

The Atlas of the Galilean Satellites therefore represents a treasure trove of all available imagery of these four moons. The further out you go, the less imagery there is: outermost Callisto gets 49 pages of plates, innermost Io, with all its interesting volcanoes, gets 89. Despite the inevitable blurry patches, there are some extraordinarily high-detail images here. One problem, though, is that the global maps are unlabelled; I found it difficult to place features that were labelled on the quadrangle, regional and detail maps in their global context. Also worth noting is that—and I suspect this is the norm for extraterrestrial mapping—these are not maps per se, but spacecraft imagery labelled and put on a map projection.

One issue that has been noted elsewhere—for example, in Emily Lakdawalla’s review last November—is that several copies of this book have been defective, with pages falling out. My own copy is fine, but seems a bit fragile. (UPDATE: Laying it open flat once was enough for several pages to come loose.) The signatures appear to be glued rather than sewn—a textbook example of the badly built British book—which is inexplicable given the size of the book and weight of the glossy paper, to say nothing of its cost. Because, at $165 (£95) list, this book is extremely expensive; ebook versions are just as exorbitant. Cheaper copies can be found elsewhere with a little digging: I got mine via AbeBooks for less than $30, shipping included. Honestly, given the risk of the book falling apart on you, that’s the way to go.

This atlas isn’t really aimed at beginners or people with a casual interest in the solar system. The price reflects that, as does its rather technical nature and organization. Those with a serious jones for the solar system will not be deterred by these or any other reservations.

Previously: Blogs and a Book About Maps of the Solar System’s Moons.