Daniel Huffman writes that “there are certain cartographic conventions out there for which I don’t understand the logic.” (Such as that thematic or choropleth maps should be on equal-area projections.) “I do not suggest that these conventions are wrong; only that I lack a clear, intuitive rationale for following them, and so haven’t always incorporated them into my own practice. Maybe you can help explain them, or maybe you’re confused, too.”

Tag: choropleth

Review: North American Maps for Curious Minds

North American Maps for Curious Minds, written by Matthew Bucklan and Victor Cizek and featuring maps and illustrations by Jack Dunnington, is the second book in the Maps for Curious Minds series: Brilliant Maps for Curious Minds came out in 2019, and Wild Maps for Curious Minds is scheduled to come out this fall. The formula appears to be the same across all three books: 100 maps and infographics, divided by theme into chapters. In the case of North American Maps for Curious Minds, the 100 maps are sorted into seven chapters: Geography; Politics and Power; Nature; Culture and Sports; People and Populations; Lifestyle and Health; and Industry and Transport.

North American Maps for Curious Minds, written by Matthew Bucklan and Victor Cizek and featuring maps and illustrations by Jack Dunnington, is the second book in the Maps for Curious Minds series: Brilliant Maps for Curious Minds came out in 2019, and Wild Maps for Curious Minds is scheduled to come out this fall. The formula appears to be the same across all three books: 100 maps and infographics, divided by theme into chapters. In the case of North American Maps for Curious Minds, the 100 maps are sorted into seven chapters: Geography; Politics and Power; Nature; Culture and Sports; People and Populations; Lifestyle and Health; and Industry and Transport.

The series is a spinoff of the Brilliant Maps website, and can be seen as an attempt to render viral map memes in book form: if this book is any indication, the maps themselves are the sort that tend to get shared across social media platforms. One I recognized right away was no. 8: the first country you’ll reach going east or west from every point on the coast. Their appearance between hard covers is to be honest a bit unexpected, and to be honest, the translation from screen to page doesn’t always work.

Continue reading “Review: North American Maps for Curious Minds”

CDC Vaccination Maps

Maps tracking the progress of the U.S.’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign at the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker (now) include an interactive county-level map showing first and second doses among 12+, 18+ and 65+ populations and a map of vaccine equity (above): a bivariate choropleth map showing the relationship between vaccination coverage and social vulnerability (housing, vehicle access, general poverty).

‘Empty Land Doesn’t Vote’ and Other Hot Takes

The hot takes about the New York Times’s detailed map of the 2016 U.S. presidential election results (see previous entry) have been coming in fast. Most of the critiques focus on the map’s failure to address population density: a sparsely populated but huge precinct appears to have more significance than a tiny district crowded by people. See, for example, Andrew Middleton’s post on Medium, Keir Clarke’s post on Maps Mania or this post on Wonkette—or, for that matter, a good chunk of cartographic Twitter for the past few days. (It’s not just Ken, is what I’m saying.)

The responses to those critiques generally do two things. They point out that the map had a specific purpose—as the Times’s Josh Katz says, “we wanted to use the 2016 results to make a tool that depicted the contours of American political geography in fine detail, letting people explore the places they care about block by block.” As he argues in the full Twitter thread, showing population density was not the point: other maps already do that. Others explore the “empty land doesn’t vote” argument: Tom MacWright thinks that’s “mostly a bogus armchair critique.” Bill Morris critiques the “acres don’t vote” thesis in more detail.

Relatedly, Wired had a piece last Thursday on the different ways to map the U.S. election results, in which Ken Field’s gallery of maps plays a leading role.

Previously: The New York Times’s Very Detailed Map of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.

The New York Times’s Very Detailed Map of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

It’s 2018. The 2016 U.S. presidential election is nearly two years in the past. But that didn’t stop the New York Times from unleashing a new map of the 2016 election results earlier this week. On the surface it’s a basic choropleth map: nothing new on that front. But this map drills down a bit further: showing the results by precinct, not just by county. The accompanying article sets out what the Times is trying to accomplish: “On the neighborhood level, many of us really do live in an electoral bubble, this map shows: More than one in five voters lived in a precinct where 80 percent of the two-party vote went to Mr. Trump or Mrs. Clinton. But the map also reveals surprising diversity.”

Kenneth Field has some objections to the map. “So you have smaller geographical areas. Detailed, yes. Accurate, certainly. Useful? Absolutely not because of the way the map was made.” It’s a choropleth map that doesn’t account for population: “An area that has 100 voters and 90 of them voted Republican is shown as dark red and a 90% share. Exactly the same symbol would be used for an area that has 100,000 voters, 90,000 of whom voted Republican.” It gets worse when that thinly populated precinct is geographically larger. (Not only that: the map uses Web Mercator—it is built with Mapbox—so Alaska is severely exaggerated at small scales.) There are, Ken says, other maps that account for population density (not least of which his own dot density map).

The Times map has a very specific purpose, and Ken is going after it for reasons that aren’t really relevant to that purpose. The map is aimed at people looking at their own and surrounding neighbourhoods: the differences in area and population between a precinct in Wyoming and a precinct in Manhattan wouldn’t normally come up. It works at large scales, whereas Ken’s point is more about small scales: zoom out and the map becomes misleading, or at the very least just as problematic as (or no more special than) any other, less granular choropleth map that doesn’t account for population. The map isn’t meant to be small-scale, doesn’t work at small scales, but then people regularly use maps for reasons not intended by the mapmaker. The mistake, I suspect, is making a map that does not work at every scale available at every scale.

Update: See this post for more reactions to the map.

Advice on Choropleth Maps

Last month Lisa Charlotte Rost published a post on Datawrapper’s blog full of tips about choropleth maps: when to use them (and when not to), how to make them better (lots about colour use), along with some examples of good ones. Worth bookmarking.

She followed that up with another post focusing on one particular factor: the size of the geographic unit. Choropleth maps that shows data by municipality, county, region, state or country will look quite different, even if they show the same data. Averages tend to cancel out extremes. She gives the following examples:

Examples of Multivariate Maps

Jim Vallandingham looks at multivariate maps:

There are many types of maps that are used to display data. Choropleths and Cartograms provide two great examples. I gave a talk, long long ago, about some of these map varieties.

Most of these more common map types focus on a particular variable that is displayed. But what if you have multiple variables that you would like to present on a map at the same time?

Here is my attempt to collect examples of multivariate maps I’ve found and organize them into a loose categorization. Follow along, or dive into the references, to spur on your own investigations and inspirations!

Jim’s examples of maps that display more than one variable include 3D maps, multicolour choropleth maps, multiple small maps, and embedded charts and symbols. Useful and enlightening.

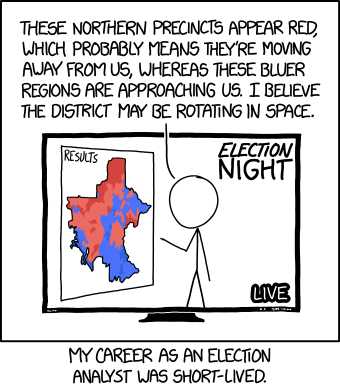

xkcd’s Relativistic Election Maps

I’m surprised it took as look as it did for physics and cartography to collide—relativity and choropleth maps—in an xkcd cartoon.

Mapping the 2017 French Presidential Election (First Round)

France held the first round of its presidential election this past Sunday. Unlike U.S. presidential elections, it’s by popular vote, with the top two vote-getters moving on to a second round in two weeks’ time.

The major candidates’ support was distributed unevenly around the country. Media organizations used several different methods to show this. The New York Times used a choropleth map, showing who among five candidates (including Lassalle, excluding Hamon, who finished fifth but does not appear to have won a commune: ouch) finished first on a commune-by-commune basis. Of course, when you have four candidates finishing within a few points of one another, when you win a district, you don’t necessarily win by much. The print edition of Le Figaro included choropleth maps detailing five candidates’ regional support as well.

#cartographie de la #Presidentielle2017 Et le futur duel #macron vs #lepen à lire demain dans @Le_Figaro pic.twitter.com/cP0kEmOPsE

— Guillaume Balavoine ?? (@gbalavoine) April 24, 2017

Both the Times and Le Figaro use geographical maps, which can be misleading because of the number of votes concentrated in large cities, as Libération’s Julien Guillot points out. (This comes up in most countries’ elections, to be honest—certainly the ones where it’s the popular vote, rather than the constituency, that’s being looked at.) Slate uses a cartogram to compensate for that. (Both of these pages are in French.)

For those seeking local results rather than analysis, several French media organizations provide them through a very similar map interface: see, for example, the online results pages for France 24, Le Figaro and Le Monde. Each begins with a map of France: clicking on a département provides results for that département that includes a map showing each commune, which can also be clicked on. For some reason neither France 24 nor Le Monde show actual vote totals at the local level, which doesn’t seem sensible in an election by popular vote.

Finally, a couple of outliers. This page looks at the results from all presidential elections under the French Fifth Republic. And this page marks the 56 communes in which Marine Le Pen received not a single vote.

3D Election Maps

Mapping U.S. election results by county and state is a bit different than mapping results by electoral or congressional district, because counties and states don’t have (roughly) equal populations. Choropleth maps are often used to show the margin of victory, but to show the raw vote total, some election cartographers are going 3D.

Max Galka of Metrocosm has created an interactive 3D map of county-level results (above) using his Blueshift tool. The resulting map, called a prism map, uses height to show the number of votes cast in each county.

Here’s a similar 3D interactive map, but using state-level rather than county-level data, by Sketchfab member f3cr204. [Maps on the Web]

A Primer on Election Map Cartography

With less than two weeks before the 2016 U.S. presidential election, it’s time for a refresher on election map cartography, particularly in the context of U.S. presidential elections.

Cartograms

Let’s start with the basics: at All Over the Map, Greg Miller explains the problem with U.S. presidential election maps—big states with few electoral votes look more important than smaller states with more votes—and introduces the idea of the cartogram: a map distorted to account for some variable other than land area.

Here are some cartograms of the 2012 U.S. presidential results (see above). Previously: Cartograms for the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election Results.

The Map That Started It All

Back in 2014, Susan Schulten looked at the map that may have started it all: an 1883 choropleth map of the 1880 U.S. presidential results (see above) that shows results not only on a county-by-county basis, but also the amount the winning candidate won by.

The map may not look advanced today, but in 1883 it broke new ground by enabling Americans to visualize the spatial dynamics of political power. Readers responded enthusiastically. One reviewer pointed to the Republican counties in Arkansas—something left invisible on a map of the Electoral College returns—and wondered what other oddities of geography and history might be uncovered when election returns were more systematically measured. In other words, the map revealed spatial patterns and relationships that might otherwise remain hidden, or only known anecdotally. Perhaps its no coincidence that at the same time the two parties began to launch more coordinated, disciplined, nationwide campaigns, creating a system of two-party rule that we have lived with ever since.

(This map also inverts the modern colours for the two main U.S. political parties: here the Democrats are red and the Republicans are blue. Those colours were standardized only fairly recently.) [Geolounge]

Rethinking Election Map Design

Back to Greg Miller, who has a roundup of different kinds of election maps throughout history, including the maps we’ve seen here so far, Andy Woodruff’s value-by-alpha maps (previously) and others.

For other ways of mapping election results, see this gallery of thematic maps, which includes things like 3D choropleth maps, dot density maps, and all kinds of variations on cartograms and choropleth maps. There’s more than one way to map an election. [Andy Woodruff]

Mapping the EU Referendum Results

Maps of the results of the United Kingdom’s referendum on remaining in the European Union show several different ways of presenting the results.

The BBC’s election night map is bare-bones, showing which side won which local authority, but not by how much. Appropriate for the moment, and for finding your locality, but not necessarily very revealing.

The New York Times’s map, another example of the fine work done by their graphics department, is a choropleth map that indicates the margin of victory in each local authority. It shows the intensity of the win by each side. (The Times does something similar with a hexagon grid map.)

But the EU referendum isn’t like a general election, where each electoral district has roughly the same population, and counts the the same in parliament. In this case it’s the raw vote numbers that count, and local districts can vary in size by as much as a couple of orders of magnitude. So the Guardian’s approach (at right), a hexagon grid that combines a choropleth map with a cartogram to show both the margin of victory and the size of the electorate, is probably most fit for purpose in this case.

I’m actively looking for other maps of the EU referendum results. Send me links, and I’ll update this post below.

Mapchart

Mapchart is a quick and dirty way to make choropleth and other coloured outline maps for online use: choose a map (world, continents, some countries), assign a colour to the state, province or country, build a legend, export to image. [Boing Boing]

Immigrants in France

Le Télégramme, a French newspaper based in Brittany, maps the percentage of immigrants in France by canton; a second map shows the largest source of immigration (Portugal shows up more than any other country). In French. [Maps Mania]

Data Visualization’s ‘Dirty Little Secret’ and Choropleth Maps

The Washington Post’s Christopher Ingraham compares two choropleth maps of U.S. population growth: while they look rather different, they use the same data. “The difference between my map and Pew’s—again, they both use the exact same data set—underscores a bit of a dirty little secret in data journalism: Visualizing data is as much an art as a science. And seemingly tiny design decisions—where to set a color threshold, how many thresholds to set, etc.—can radically alter how numbers are displayed and perceived by readers.” [Andy Woodruff]

(Worth mentioning that this is exactly the sort of thing dealt with in Mark Monmonier’s How to Lie with Maps.)