News of Boston public schools’ decision to go with the Peters projection has gone viral over the past week, and my teeth have not stopped itching. Largely because this is very much old news: Arno Peters began promoting “his” projection 44 years ago, and the Peters map has been making the rounds in certain circles ever since then. This is not new, and the media is showing its feckless streak in its lack of awareness of that fact. After all, the West Wing episode with the Peters map in it was broadcast 16 years ago.

The Gall-Peters projection is just one of several rectilinear equal-area projections; that Peters promoted it as a tool of social justice and anti-colonialism made it awfully appealing to people who are concerned with such issues. (They are not wrong to be concerned with such issues.) But cartographers have generally always been appalled by the projection, by Peters’s rhetoric and by his general ignorance of what had gone before. (Peters’s map had already been described by James Gall in 1885; the Mercator projection‘s insufficiencies as a wall map had long been known; and there were many other projections, from the Van der Grinten to the Mollweide to the Goode homolosine, that were already being used in the Mercator’s stead.)

(The Mercator projection, for its part, makes a crap wall map: its virtue is that rhumb lines—compass headings—are straight lines, making the Mercator ideal for navigation. It’s worth emphasizing that Mercator himself died in 1594. Again, see Monmonier’s book on the subject.)

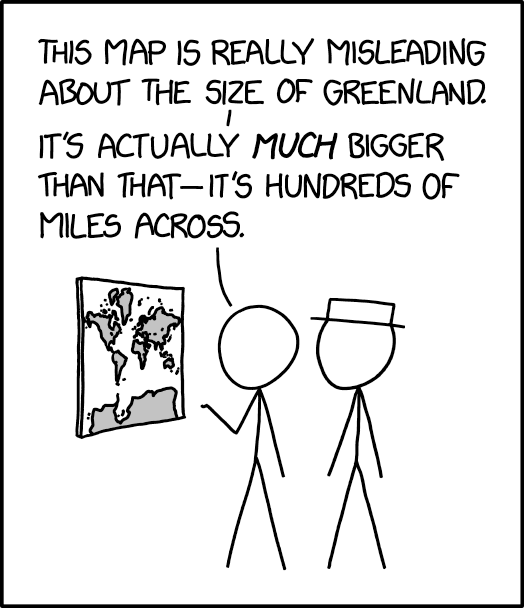

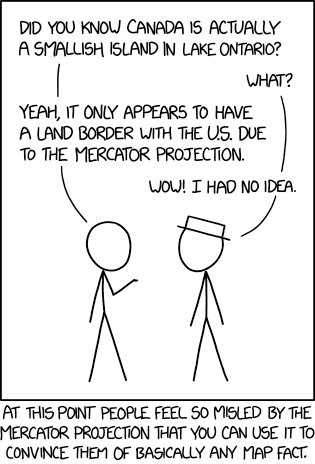

Cartographers’ response to the Peters projection is essentially, usually (and correctly) that every map projection is a compromise, because every map projection is an attempt to represent a round planet on a flat surface. All maps, in other words, lie; or at least no map is exempt from lying; or at least the Mercator is no more a liar than any other projection. It’s essentially an effort in debunking—the tedious repetition of “well, actually” to a credulous audience that doesn’t care enough to listen all the way through. (And besides: the company selling the Peters map thoroughly agrees with them!)

For the latest examples of this, see Caitlin Dempsey’s piece on teaching context, and Andy Woodruff’s response to the latest round of this. They’re good pieces, worth reading—but I can’t help wonder whether something different needs to be tried. But then again: what problem are we trying to solve? Media and public credulity? The fact that the Peters projection, bluntly, sucks? The campaign—and it is a campaign—behind it?

But the campaign for the Peters map is increasingly irrelevant. In late 2015 I argued that the debate over the right projection for wall maps was the cartographic equivalent of fighting the last war. The Peters map was a 20th-century response to a 19th-century problem (the Mercator on wall maps) that had already largely been solved earlier in the century. Sure, there are still wall maps out there that use the projection (I’m looking in your direction, IKEA), but by and large it’s not used nearly as much as the Peters defenders would have you think.

But 21st-century mapmaking is not about wall maps: it’s about web maps. As I said in 2015:

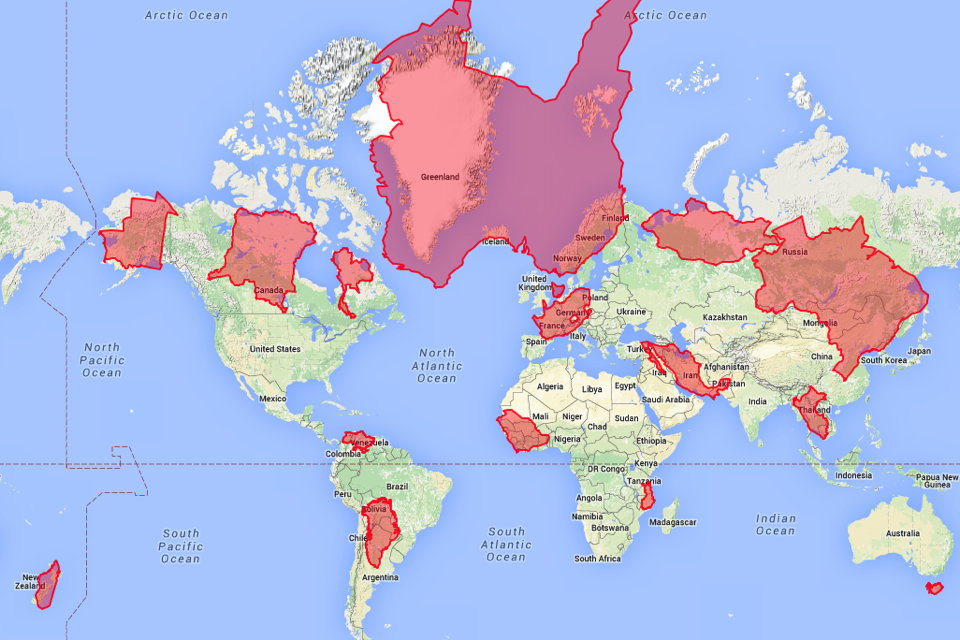

Every online map service uses a variant of the Mercator projection called Web Mercator. Whatever its shortcomings—and there are many, owing to the fact that its calculations use a spherical Mercator model to save computational cycles—Web Mercator has become the de facto standard. And the size distortions at small scales that have made the Mercator projection the target of so much ire over the decades are simply moot for most use cases.

In many ways the past debates over the Mercator are moot: arguing over the right projection for wall-sized world maps—Mercator vs. Peters vs. Robinson—is fighting the last war. Mercator has become the default option for online mapmaking, simply because so many data visualization maps rely on Google Maps or OpenStreetMap for their base map layer. Other projections will be reserved for the professionals, people with access to more sophisticated mapmaking tools and the skill to use them, but for the most part, when data is mapped on the Internet, it’ll be mapped according to Mercator.

Zoom out in Google Maps or OpenStreetMap, and what do you see? The Mercator projection, with Greenland in all its inappropriately giant glory. (Apple Maps turns into a globe when you zoom out far enough, but Apple Maps are app-only.) The reason why this isn’t generally seen as a problem is that hardly anyone uses Google Maps as a world map: like topographic maps that use UTM, at close range Mercator works just fine.

While there are efforts under way to use other projections in web maps, it’s unlikely that the Mercator-vs.-Peters battle—a false dichotomy if there ever was one—will migrate to the digital arena.

Previously: The Peters Projection Comes to Boston’s Public Schools; In Defence of the Mercator Projection; How the Mercator Projection Won the Internet.