Starkey Comics’s Map of British English Dialects took Ryan ages to research. “The end result is an image which is, to my knowledge, the most detailed map of British dialects ever made. But it is still very much unfinished, and it always will be.” The rest of his post is a careful litany of caveats about what constitutes a dialect, whether it’s geographically specific and whether its boundaries can be sharply defined. “So yes, this map may be unsatisfying, arbitrary, and unfinished, and no amount of work on it will really change that. It exists mainly as a testament to the huge dialectal diversity of the English language within the UK, and as a way for me to express my fascination and love for that diversity.” [LanguageHat]

Starkey Comics’s Map of British English Dialects took Ryan ages to research. “The end result is an image which is, to my knowledge, the most detailed map of British dialects ever made. But it is still very much unfinished, and it always will be.” The rest of his post is a careful litany of caveats about what constitutes a dialect, whether it’s geographically specific and whether its boundaries can be sharply defined. “So yes, this map may be unsatisfying, arbitrary, and unfinished, and no amount of work on it will really change that. It exists mainly as a testament to the huge dialectal diversity of the English language within the UK, and as a way for me to express my fascination and love for that diversity.” [LanguageHat]

Category: Linguistics

New Approaches to Ethno-Linguistic Maps

Back in 2017, Matthew Cooper wrote a post discussing the problems with language maps and outlined some ways to make better maps of language distributions.

One major issue with most modern maps of languages is that they often consist of just a single point for each language – this is the approach that WALS and glottolog take. This works pretty well for global-scale analyses, but simple points are quite uninformative for region scale studies of languages. Points also have a hard time spatially describing languages that have disjoint distributions, like English, or languages that overlap spatially. […]

One reason that most language geographers go for the one-point-per-language approach is that using a simple point is simple, while mapping languages across regions and areas is very difficult. An expert must decide where exactly one language ends and another begins. The problem with relying on experts, however, is that no expert has uniform experience across an entire region, and thus will have to rely on other accounts of which language is prevalent where. […]

I believe that, thanks to greater computational efficiency offered by modern computers and new datasets available from social media, it is increasingly possible to develop better maps of language distributions using geotagged text data rather than an expert’s opinion. In this blog, I’ll cover two projects I’ve done to map languages—one using data from Twitter in the Philippines, and another using computationally-intensive algorithms to classify toponyms in West Africa.

Map of Common Gaelic Placenames

Phil Taylor’s Map of Common Gaelic Placenames applies the Ordnance Survey’s guide to the Gaelic origin of place names and places them on early 20th-century OS maps of Scotland.

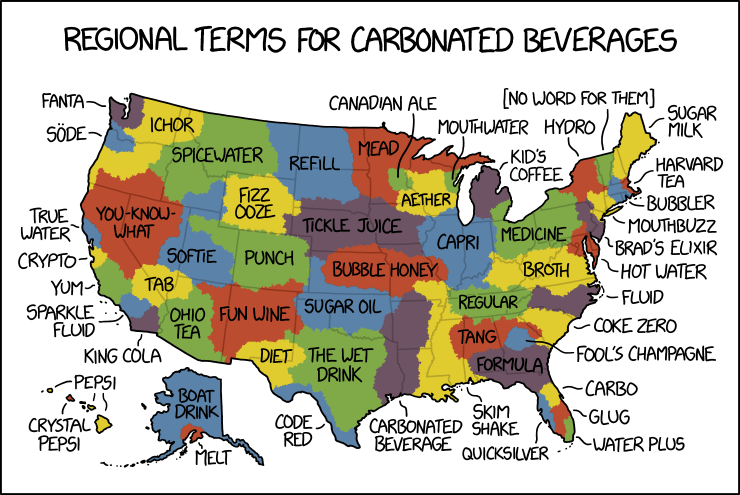

Pop vs. Soda Maps Spoofed by xkcd

By law, I am required to share every xkcd comic about maps. Today’s makes great fun of pop versus soda maps—the maps showing where in the U.S. carbonated beverages are referred to as pop versus where they’re referred to as soda. Randall takes things to their ludicrous extremes, as he is, by law, required to do.

Map of Indigenous Canada Accompanies People’s Atlas

The map accompanying the Indigenous People’s Atlas of Canada is a map of Indigenous Canada: as iPolitics’s Anna Desmarais reports, “Dotting the map are the names of Indigenous languages, including Cree and Dene, and the geographical location where each language is spoken. The size of the word, officials said, depends on how big the Indigenous population is in a given region.” Meanwhile, the names and borders of provinces and territories are apparently absent, and the only cities that appear on the map are the ones with substantial Indigenous populations. It sounds marvellous. [WMS]

Previously: The Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada.

Ben Smith’s Maps of British Stream Names

Streams in Great Britain have many different names—brook, burn, stream, water—and it turns out that the variations are regional. On Twitter, Ben Smith has been posting maps of Britain’s obscure and idiosyncratic stream names. Atlas Obscura has more, and also points to Phil Taylor doing something similar with Britain’s lakes. Language maps, meet toponyms. [Benjamin Hennig]

The Algonquian Linguistic Atlas

The Algonquian Linguistic Atlas, a collaborative, interactive web-based map that provides phrases in various indigenous languages in Canada, has earned its project director, Carleton University linguistics professor Marie-Odile Junker, a Governor General’s Innovation Award, CBC News reported in May.

The Great American Word Mapper

Like The United Swears of America, The Great American Word Mapper explores regional variation in English language use in the United States based on geocoded Twitter data, this time through a search interface that allows side-by-side comparisons. As before, forensic linguist Jack Grieve is involved, along with fellow linguist Andrea Nini. [Kottke]

Previously: Speaking American; The United Swears of America.

Mi’kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas

A guide to Mi’kmaw place names in Nova Scotia, the Mi’kmaw Place Names Digital Atlas was unveiled last year. It’s “an interactive map showing more than 700 place names throughout Nova Scotia, and includes pronunciation, etymology, and other features, such as video interviews with Mi’kmaw Elders.” Flash required (really?). [CBC News]

Speaking American

Based on an interactive dialect quiz in the New York Times that generated more than 350,000 responses, Josh Katz’s Speaking American: How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk: A Visual Guide “offers a visual atlas of the American vernacular—who says what, and where they say it—revealing the history of our nation, our regions, and our language.” Out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Buy at Amazon.

Based on an interactive dialect quiz in the New York Times that generated more than 350,000 responses, Josh Katz’s Speaking American: How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk: A Visual Guide “offers a visual atlas of the American vernacular—who says what, and where they say it—revealing the history of our nation, our regions, and our language.” Out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Buy at Amazon.

The United Swears of America

Linguist Jack Grieve studies regional variations in languages using quantitative methods. A year ago he posted a number of maps of the United States showing regional variation in swear word usage, based on a corpus of nearly nine billion geocoded tweets. Stan Carey of the Strong Language blog has more on the maps:

Hell, damn and bitch are especially popular in the south and southeast. Douche is relatively common in northern states. Bastard is beloved in Maine and New Hampshire, and those states—together with a band across southern Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas—are the areas of particular motherfucker favour. Crap is more popular inland, fuck along the coasts. Fuckboy—a rising star—is also mainly a coastal thing, so far.

I love everything about this. See also Stan’s follow-up post from last March. (Thanks to Natalie for finding this.)

Mapping the Decline of English Dialects

Using a mobile app launched last January (iPhone, Android), similar to the one used to study Swiss German dialect usage, Cambridge researchers have amassed a huge dataset of English language usage and are using it to map the decline in regional dialect words and pronunciations. [The Telegraph]

Mapping Swiss German Dialects

Researchers are mapping the shift in Swiss German dialect usage via an iOS app. The app asks users to take a 16-question survey based on maps from a language atlas that mapped Swiss German usage circa 1950. The app predicts the user’s actual home dialect location based on those maps; differences between that prediction and the user’s actual home dialect location reveal how Swiss German has changed over time. They ended up getting responses from 60,000 speakers. PLOS ONE article. [via]