Mark Monmonier’s How to Lie with Maps has always been about how to read maps, not how to make them. The map-using public is inclined not only to believe what’s on the map, but to trust it: why would so many people willingly drive their cars into ditches, if they didn’t trust their cars’ navigation systems more than their own eyes? Monmonier prescribes “a healthy skepticism” about maps, and this book is a tool to that end: “I want to make readers aware that maps, like speeches and paintings, are authored collections of information and are also subject to distortions arising from ignorance, greed, ideological blindness, or malice.” The book is essentially a cheat sheet, showing all the ways that maps can be made to shade, or at the very least, select the truth. At the minimum, mapmakers must decide what to include or exclude, and those decisions may not necessarily be honest or fair.

Mark Monmonier’s How to Lie with Maps has always been about how to read maps, not how to make them. The map-using public is inclined not only to believe what’s on the map, but to trust it: why would so many people willingly drive their cars into ditches, if they didn’t trust their cars’ navigation systems more than their own eyes? Monmonier prescribes “a healthy skepticism” about maps, and this book is a tool to that end: “I want to make readers aware that maps, like speeches and paintings, are authored collections of information and are also subject to distortions arising from ignorance, greed, ideological blindness, or malice.” The book is essentially a cheat sheet, showing all the ways that maps can be made to shade, or at the very least, select the truth. At the minimum, mapmakers must decide what to include or exclude, and those decisions may not necessarily be honest or fair.

The first edition of How to Lie with Maps came out in 1991, the second in 1996. (See my review of the second edition here.) Since then the cartographic landscape is much changed: the map a person may use most frequently may come via their phone rather than paper. But the advice found in this book is still valid. What goes for a paper map is still relevant to the map you call up on your iPhone. And so now, 22 years later, we have a third edition of How to Lie with Maps, which came out from the University of Chicago Press last April. For the most part it’s familiar territory. Other than a nip and tuck here and there and a few new chapters at the end, it’s largely the same book it was in 1996. How does it measure up in the present moment?

Mostly well, with some caveats. The core message of How to Lie with Maps will not become obsolete until maps do, which is to say never; but the examples and emphases are starting to become a bit dated. The reader might have to do a little more work in some cases to see the applicability of a chapter—to translate it into familiar terms—but that effort will be rewarded. For example, I think that everyone working with web-based maps should become quite familiar with chapter 3, “Map Generalization,” for its insights on what to include and exclude at different scales. The chapter on data maps, discussing the use of choropleths, cartograms and other data visualizations, is absolutely essential: so many of the maps being circulated as memes are data maps of some kind, and anything that improves the critical eye with regard to such maps is going to help.

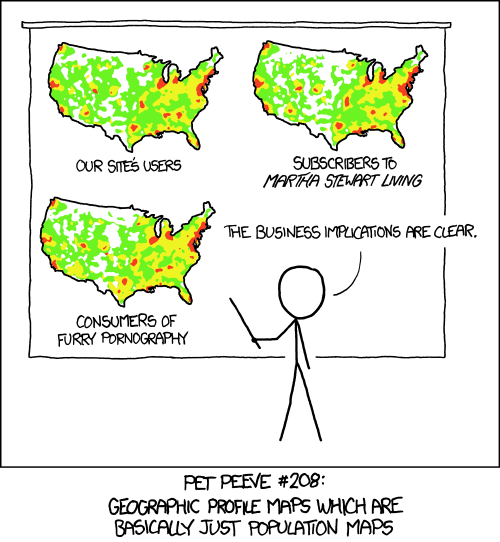

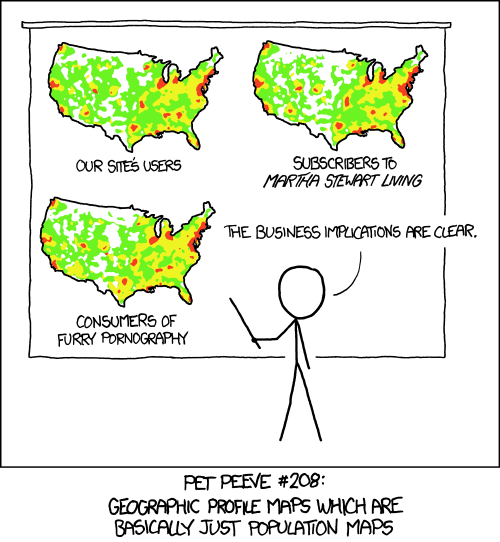

But that chapter on data maps does get a bit lost in the weeds, especially for the general reader. And I’d have liked to have seen something on heat maps akin to this xkcd cartoon:

Bad internet maps have been described as a “social media plague”: they’re popular, they’re insidious, and they’re often not even wrong. But they’re not specifically dealt with in How to Lie with Maps, and that’s a blind spot: in the era of fake news, hoaxes and state-sponsored mendacity, maps that go viral are the ones most in need of a vaccination campaign.

Instead, the new chapters focus on image maps (satellite and aerial imagery), prohibitive cartography (which seems out of place here, and seems more a summary of Monmonier’s other work) and “fast maps,” which is more about web-based mapping than the stuff that gets shared on social media. The new chapters are noticeably more concise than the old. The net effect is a book that is still important, still relevant and still badly needed, but whose updates don’t quite bring it up to the present.

I received a review copy from the publisher.

Amazon | iBooks