The Taxi Brains Project explores whether London taxi drivers’ legendary ability to navigate could help diagnose dementia. London cabbies, who since 1865 start by spending three or four years memorizing the London road network in order to learn the Knowledge, have been found to have an enlarged hippocampus, the part of the brain involved in spatial memory. Meanwhile, the hippocampus shrinks in Alzhemier’s patients. Studying the cabbies’ enlarged hippocampi may offer insights that could improve early detection. The study is seeking drivers to take tests and get an MRI scan. See the Washington Post’s story for details. [WMS]

Category: Navigation

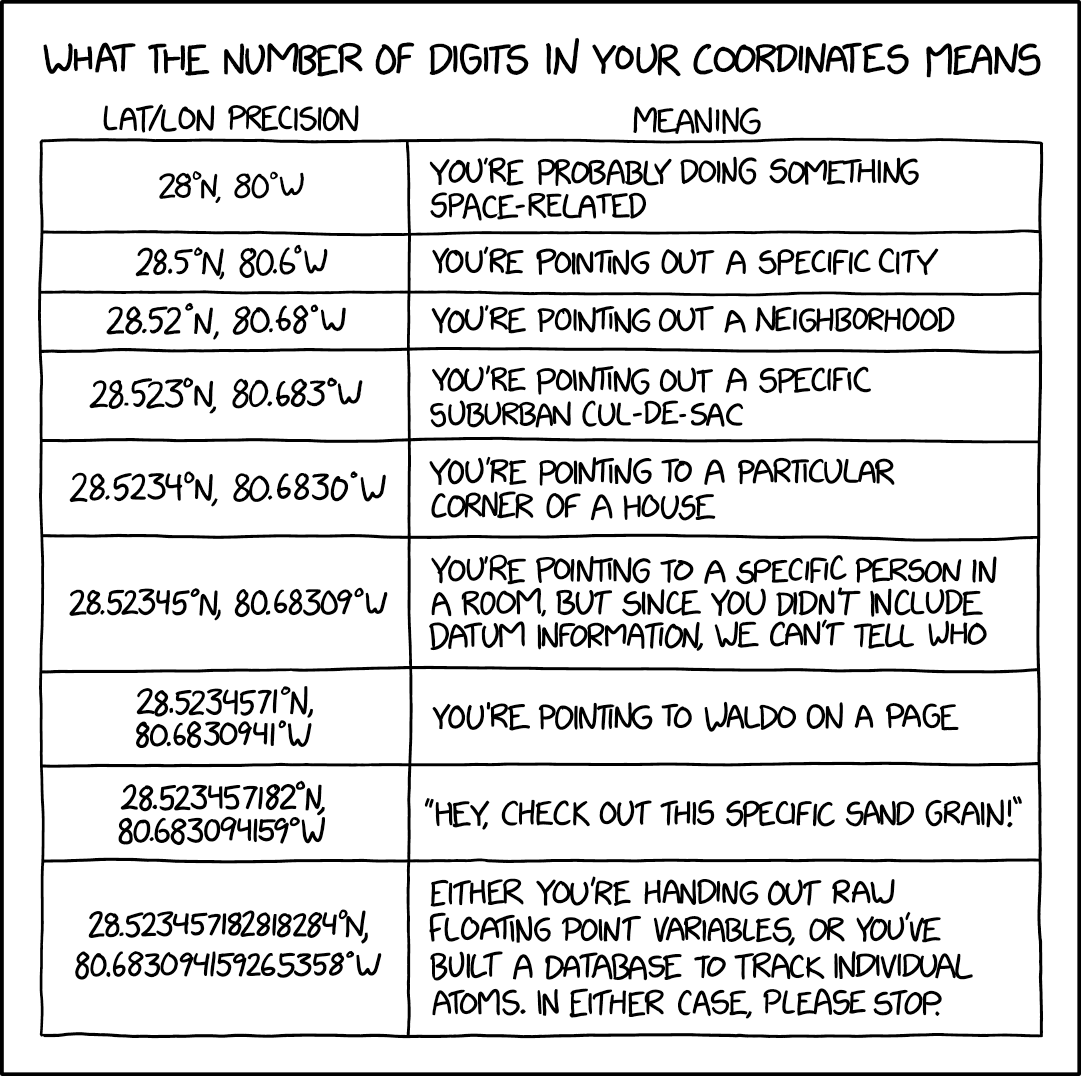

Latitude, Longitude and Decimal Points

Vladimir Agafonkin’s post, which demonstrates just what latitude and longitude to x decimal places looks like, is a visual complement to xkcd’s comic about coordinate precision: both tell you that when it comes to latitude and longitude, more than a few decimal points is pointless. “As you’ve probably guessed, 6 digits should be enough for most digital cartography needs (spanning around 10 centimeters). Maybe 7 for LiDAR, but that’s it.”

Four Articles on Navigating Outdoors

Outside’s Andrew Skurka has posted a four-part series on the skills and tools required to navigate outdoors (remember outdoors?), which in general means knowing how not to get lost. In part one, “A Backpacker’s Guide to Maps,” Skurka recommends what kind of maps to take with you: paper maps, mainly, of various scales, but with digital maps as a backup. Part two, “The Gear You Need to Navigate in the Backcountry,” looks at equipment: not just GPS, but also basics like a compass, altimeter and a watch. In part three, “How to Master Navigational Storytelling,” is about developing a narrative of the route you’re taking to avoid getting lost. Finally, Skurka offers a checklist of skills to test yourself against.

Previously: The Lost Art of Finding Our Way.

xkcd on Coordinate Precision

In Monday’s xckd, Randall Munroe points out that when it comes to coordinate precision, there is such a thing as too many decimal places.

Wayfinding: A New Book about the Neuroscience of Navigation

M. R. O’Connor’s book Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World came out in April from St. Martin’s Press. Not coincidentally, she’s published a couple of pieces on the subject of that book, both of which focus on humans’ ability to pay attention to their surroundings, and the effect that relying on GPS directions might have on that ability. In a piece for Undark, O’Connor argues that “our unshakeable trust in GPS,” which traces itself back through hundreds of years of believing in the infallibility of maps, gets us lost because we’re relying on the device rather than our senses. Her piece for the Washington Post focuses on the role of the hippocampus in navigation and spatial awareness, and the need to exercise that part of the brain.

M. R. O’Connor’s book Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World came out in April from St. Martin’s Press. Not coincidentally, she’s published a couple of pieces on the subject of that book, both of which focus on humans’ ability to pay attention to their surroundings, and the effect that relying on GPS directions might have on that ability. In a piece for Undark, O’Connor argues that “our unshakeable trust in GPS,” which traces itself back through hundreds of years of believing in the infallibility of maps, gets us lost because we’re relying on the device rather than our senses. Her piece for the Washington Post focuses on the role of the hippocampus in navigation and spatial awareness, and the need to exercise that part of the brain.

This is not the first book on the subject: Greg Milner published Pinpoint in 2016 (previously). See also: Satnavs and ‘Switching Off’ the Brain.

More on the Pros and Cons of Paper Maps

The flurry of articles defending paper maps continues, and it can be tricky to separate them from one another: some are in the context of the Standfords store move; others are reprints of Meredith Broussard’s Conversation piece. But Sidney Stevens’s essay for Mother Nature Network is its own thing. It acknowledges both the downsides of paper maps (they get damaged and outdated) and the advantages of digital maps (“GPS”) before looking at the advantages of paper maps. It’s well-researched and well-considered.

Technochauvinism, Deep Knowledge and Paper Maps

Paper maps continue to find their defenders. The latest is Meredith Broussard, author of Artificial Unintelligence. In a piece for The Conversation, she applies her argument against what she calls “technochauvinism”—the idea that the digital and the technological are always better—to mapmaking. “Technochauvinists may believe that all digital maps are good,” she writes, “but just as in the paper world, the accuracy of digital maps depends entirely on the level of detail and fact-checking invested by the company making the map.” Errors on paper maps are more forgivable because, she argues, we recognize that paper maps fall out of date.

She also distinguishes between surface and deep knowledge, and associates digital maps with the former and paper maps with the latter, but there’s a risk of getting cause and effect spun around. “A 2013 study showed that, as a person’s geographic skill increases, so does their preference for paper maps,” she writes; but it doesn’t follow that paper maps lead to geographic skill. Those with poor map-reading abilities may do the bare minimum required to navigate, and nowadays that means using your phone. [WMS]

World Magnetic Model Being Updated a Year Early

The World Magnetic Model—the standard model of the Earth’s magnetic field and a crucial part of modern navigation systems—was last updated in 2015. That update was supposed to last until 2020, but problems with the model started within a year of the last update. As Nature reports, a geomagnetic pulse under South America in 2016 made the magnetic field “lurch”:

By early 2018, the World Magnetic Model was in trouble. Researchers from NOAA and the British Geological Survey in Edinburgh had been doing their annual check of how well the model was capturing all the variations in Earth’s magnetic field. They realized that it was so inaccurate that it was about to exceed the acceptable limit for navigational errors.

As a result, the WMM is being updated a year early—this month, in fact, though the U.S. government shutdown is pushing back the release of the updated model.

Old Phones, Old Maps and Old Tech

CNet’s Kent German asks people to stop tech-shaming over old phones and paper maps, though I’m not exactly sure who exactly does this (it’s not like he provides any examples). Anyway, one example he does use to bolster his argument is the time a paper map saved him from getting lost in France when his rental car’s GPS didn’t have updated maps; the graft to the larger argument in favour of not being so quick to abandon old tech in favour of the latest and greatest does leave some visible seams. (He also drags the post office into the argument. It’s Luddite potpourri.) [MAPS-L]

The argument for paper maps is getting ever more insistent, even shrill, but it seems to me to be mainly coming from the tech side of things. My impression is that the people who rely too much on mobile maps haven’t lost the ability to read maps; they never had it in the first place.

Previously: Popular Mechanics Proselytizes Paper Maps.

Popular Mechanics Proselytizes Paper Maps

Popular Mechanics: “Even in 2019, there are good reasons to own a paper map, whether it’s the kind you can grab at the gas station or a sturdy road atlas […] that lives in your car.” This is a listicle, so six reasons are given, some of which are absolute rubbish: paper maps aren’t “nearly flawless” in terms of accuracy (they do go out of date), and they’re not inherently more comparative (checking vs. online maps) than checking one online map against another (e.g. Google vs. Apple vs. OpenStreetMap). Valid points about reliability and being able to plot out your own routes, though. [CCA]

How to Navigate the Seas of a Flat Fantasy World

How does navigation work on a flat world? Admittedly this is not a question that comes up outside flat earth societies, at least not in the real world, but fantasy worlds aren’t always spherical. Tolkien’s Middle-earth, for example, started off as a flat world, but became round during a cataclysmic event. Before that, the Númenóreans (Aragorn’s ancestors, for those not totally up on their Tolkien lore) were held to be the greatest seafarers in the world: “mariners whose like shall never be again since the world was diminished,” as The Silmarillion puts it. The problem is, a flat earth has implications for navigation: many known methods simply wouldn’t work.

In a piece I wrote for Tor.com, “The Dúnedain and the Deep Blue Sea: On Númenórean Navigation,” I try to puzzle out how they could have navigated the oceans of a flat world. I come up with a solution or two, within the limitations of my math abilities. (I’m sure readers who have more math than I do will be able to come up with something better.) It assumes a certain familiarity with Tolkien’s works, and it draws rather heavily on John Edward Huth’s Lost Art of Finding Our Way, which I reviewed here, not at all coincidentally, last month.

The Lost Art of Finding Our Way

It’s become a commonplace that modern technology has eroded our ability to navigate: that relying on GPS and smartphones is destroying our brains’ abilities to form cognitive maps and that we’d be utterly lost without them.1 I’m not sure I subscribe to that point of view: plenty of people have been getting themselves lost for generations; relying on an iPhone to get home is not much different from nervously having to follow someone’s scribbled directions without really knowing where you’re going.

It’s become a commonplace that modern technology has eroded our ability to navigate: that relying on GPS and smartphones is destroying our brains’ abilities to form cognitive maps and that we’d be utterly lost without them.1 I’m not sure I subscribe to that point of view: plenty of people have been getting themselves lost for generations; relying on an iPhone to get home is not much different from nervously having to follow someone’s scribbled directions without really knowing where you’re going.

For my part, I can’t get lost. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible for me to get lost: that has, in fact, been known to happen. I mean that I can’t allow myself not to know where I am under any circumstances. I’ve got a pretty good cognitive map, but if I’m in a strange city without a map of said city, I’m deeply uncomfortable if not upset; provide me with a map to get my bearings with and I’m immediately at ease. In my case, having an iPhone—with multiple map applications—means I don’t have to get to the nearest map outlet as soon as freaking possible. It’s not, in other words, an either-or situation.

John Edward Huth is firmly in the former camp. He’s a particle physicist at Harvard who’s worked on the Higgs boson who for years has been running an interesting side gig: he teaches a course on what he has called “primitive navigation”—the ancient means of navigating the world that existed prior to the advent of some later technology. The course, and the accompanying book, The Lost Art of Finding Our Way (Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2013), are an exercise in recapturing those methods.

Are People with a Good Sense of Smell Better Navigators?

A recent study suggests that there’s a link between a good sense of smell and a good sense of direction, with the same brain areas being implicated in both abilities. As someone who has difficulty getting lost who also has a precise sense of smell, I resemble this study, which was published at Nature Communications. [Boing Boing]

The Woman Who Gets Lost Every Day

Developmental topographic disorientation is a neurological disorder that prevents people from making cognitive maps. People suffering from DTD literally get lost in familiar surroundings: their home, to and from work. As someone who literally cannot get lost, I have a hard time imagining what that could possibly be like. Enter The Woman Who Gets Lost Every Day, a short film about Sharon Roseman, a woman with DTD who shares how she experiences and navigates the world in her own words. [The Atlantic]

There have been a number of news articles on DTD since the Walrus article I told you about in 2011. See, for example, this 2015 article in The Atlantic.

Navigation: A Very Short Introduction

The problem with Jim Bennett’s Navigation: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, May 2017) is summed up in its subtitle: it’s very short, and it’s only an introduction.

The problem with Jim Bennett’s Navigation: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, May 2017) is summed up in its subtitle: it’s very short, and it’s only an introduction.

Part of Oxford University Press’s Very Short Introductions series, Navigation discusses the tools and methods used by mariners and navigators to find their way across the seas, beginning with various cultures’ ancient navigational techniques, moving through tools like cross-staffs, backstaffs and octants, dealing with the matter of longitude (on which Bennett has some opinions regarding the popular narrative), before wrapping up, too briefly, with modern techologies like radio beacons, inertial navigation and GPS.

There are some illustrations that are a great help in understanding concepts and tools whose use is not immediately obvious, but, as the subtitle suggests, this is not a book that goes into much depth. At only 144 pages—20 percent of which is taken up by front matter, glossary and index—it can only give the barest of introductions to the subject. That can be maddening for the reader, particularly when its coverage is so uneven: there’s a fair bit on the tools and techniques used during the age of sail, but only a paragraph on LORAN and Loran-C, for example. Another frustration is Bennett’s extremely discursive style, as though he were giving a posh invited lecture; I kept feeling that more could have been included had his prose been tightened up.

All the same, there’s value in a book that styles itself, modestly, as an introduction. An introduction is where you begin. It’s the first step, not the finish line. It sets out the parameters of the field and gives you just enough to know what’s out there. For someone like me, it tells me where the gaps are in my knowledge. To paraphrase someone, it lets you know what you do not know. It tells you where to go next: the most useful part of the book may well be its “Further Reading” section; you just need the preceding 116 pages of text to know how to use it.

And for all my concerns about brevity and prose, it’s a good deal more accessible, and easier to read, than the equivalent Wikipedia page—and it went through an editorial process, too. And while it’s not free, it’s very modestly priced. So I have no regrets about buying it.